In Japanese culture, tea is far more than a simple beverage; it represents a philosophical, spiritual, and aesthetic practice deeply shaped by Buddhist thought. Under the influence of Zen Buddhism, tea evolved into a medium through which ideals such as simplicity, humility, respect, and inner harmony could be experienced. The Japanese tea ceremony, with its carefully prescribed rituals and symbolic meanings, embodies this synthesis of philosophy, art, and daily life.

Influenced by Buddhism, the Japanese endowed tea with profound philosophical meaning. The first comprehensive work devoted to tea was written by Okakura Kakuzō, who explained in his book The Book of Tea (Cha-no-yu, 1906) that the Japanese elevated tea to a form of spiritual discipline, transforming it into what he described as a “religion of tea,” which he termed “Teaism.”

In Japanese culture, tea signifies far more than an act of drinking. Its preparation, presentation, and consumption take place within a framework of refined aesthetics and grace, governed by a sequence of carefully defined rules and rituals. This ceremonial practice, dating back to the fifteenth century, is known as Sadō or Chanoyu, meaning “the Way of Tea.” The foundations of the tea ceremony were laid by the Zen master Murata Shukō, who initially employed materials imported from China; over time, however, these were replaced by locally produced Japanese ceramics.

In the sixteenth century, the Zen monk Sen no Rikyū further refined the tea ceremony, transforming it into a distinct art form. Until the Meiji Period in the nineteenth century, tea ceremonies were restricted exclusively to men. With Japan’s opening to the West during the Meiji era, women were also allowed to participate in these rituals.

Inspired by Zen Buddhist teachings that emphasize inner enlightenment and spiritual purification, the tea ceremony symbolizes values such as simplicity, modesty, respect, and serenity. It is regarded as a ritual of purity and cleanliness. During the ceremony, guests detach themselves from the burdens of daily life and turn inward toward contemplation and self-awareness.

Every element of the tea ceremony is meticulously planned in advance, from the arrangement of the garden to the furnishing of the tea room. The process includes the preparation of the utensils, the lighting of the brazier, the heating of water, the making of the tea, and its presentation to the guests. In contemporary Japan, an authentic tea ceremony—still practiced today—can last approximately four hours and is conducted in specially designed rooms known as chashitsu, in the presence of invited guests.

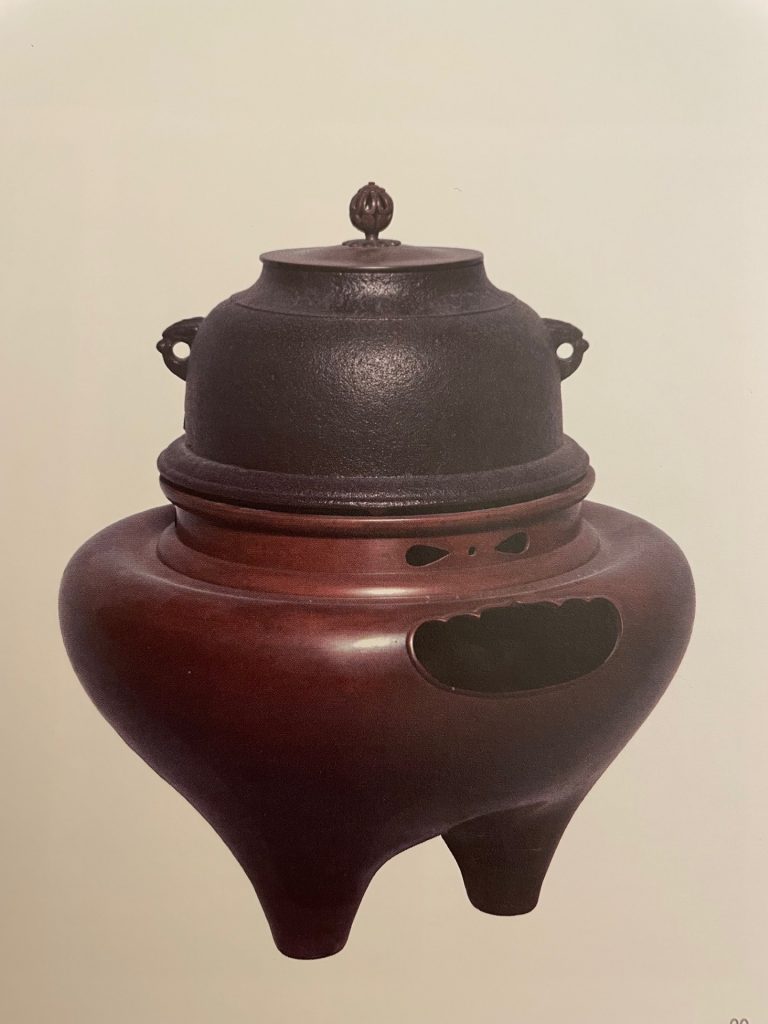

Among the essential tools used in the tea ceremony are the furo, a brazier for heating water; the chagama, a kettle; the chasen, a bamboo whisk used to mix the tea; the chawan, the tea bowl from which the tea is drunk; and the natsume, a container for storing powdered tea.

Before entering the tea room, guests leave behind all items symbolizing worldly wealth, power, or violence, including jewelry and weapons, emphasizing spiritual equality and humility.¹⁷ The host wears a special kimono known as Tsukegasa, distinguished by embossed patterns extending from the shoulders at the front to the hem at the back.¹⁸ Kneeling gracefully, the host conducts the ceremony with calm and deliberate movements, first offering sweets and confections to the guests.

Using a long, slender bamboo scoop, the host places powdered tea into a bowl, adds hot water, and whisks the mixture with a bamboo whisk. After taking a sip from the chawan, the guest wipes the rim of the bowl, bows to the next guest, and passes the bowl along.Traditionally, tea is shared from a single bowl passed among guests, symbolizing equality, mutual respect, and communal harmony.

Once all guests have taken a sip, it is customary for them to examine the utensils used during the ceremony and to offer appreciative remarks. Defined as an “art of appropriateness,” the tea ceremony is characterized by a relationship of mutual respect between host and guests, as though they were meeting one another for the final time. The ritual concludes with the host respectfully bidding farewell to the guests.

In the Japanese tea ceremony, aesthetic and philosophical principles are embedded in every detail of the experience. Tea bowls (chawan) are often intentionally asymmetrical or imperfect, reflecting the wabi-sabi ideal that values transience, humility, and beauty found in imperfection. The approach to the tea house is equally significant: the garden path (roji), with its carefully arranged stones, is designed to slow the visitor’s pace and prepare the mind for contemplation, functioning as a form of moving meditation. Central to the ceremony is the concept of ichigo ichie, the belief that each encounter is unique and will never occur again, encouraging host and guests to treat the moment with utmost care and attentiveness. Every element of the ceremony—from the choice of flowers and hanging scroll (kakemono) to the tea utensils and seasonal sweets—is selected according to the time of year, reinforcing an awareness of nature’s cycles. The host’s deliberate, unhurried movements cultivate mindfulness, guiding participants toward an inward focus on breath and presence. Today, the tea ceremony continues to be practiced and taught in Japan, not merely as a traditional art but as a form of cultural and moral education that integrates aesthetics, philosophy, and daily life into a single ritual.

The Japanese tea ceremony represents a unique fusion of Zen Buddhist philosophy, aesthetic refinement, and social ritual. Through its emphasis on mindfulness, harmony, and respect, it transforms a simple act into a profound cultural experience. Enduring from the fifteenth century to the present day, the tea ceremony continues to serve as a living expression of Japan’s spiritual and artistic traditions, offering participants a moment of tranquility and introspection within the flow of everyday life.

Dr. Humeyra Turedi

References

Japanese Wind in the Ottoman Palace (2013). TBMM Collections of National Palaces.

Japon Kültüründe Çay Töreni: Zen Felsefesi, Estetik ve Ritüel

Japon kültüründe çay, basit bir içecekten çok daha fazlasını ifade eder; Budist düşüncenin derin etkisiyle şekillenmiş felsefi, ruhsal ve estetik bir pratiği temsil eder. Zen Budizmi’nin etkisi altında çay, sadelik, alçakgönüllülük, saygı ve içsel uyum gibi ideallerin deneyimlenebildiği bir araca dönüşmüştür. Japon çay töreni, belirli kurallara bağlı ritüelleri ve sembolik anlamlarıyla, felsefe, sanat ve gündelik yaşamın bu sentezini somutlaştırır.

Budizm’in etkisiyle Japonlar çaya derin bir felsefi anlam yüklemişlerdir. Çay üzerine yazılmış ilk kapsamlı eser, Okakura Kakuzō’nun 1906 tarihli The Book of Tea (Cha-no-yu) adlı çalışmasıdır. Okakura, Japonların çayı bir ruhsal disiplin düzeyine yükselterek onu “Çay Dini” olarak nitelendirdiğini ve buna “Teaism” adını verdiğini belirtir.

Japon kültüründe çay, yalnızca içme eylemi değildir. Çayın hazırlanışı, sunumu ve içimi; zarafet ve estetik incelik çerçevesinde, dikkatle belirlenmiş kurallar ve ritüeller dizisi içinde gerçekleşir. 15. yüzyıla uzanan bu törensel uygulama, “Çayın Yolu” anlamına gelen Sadō ya da Chanoyu olarak adlandırılır. Çay töreninin temelleri Zen ustası Murata Shukō tarafından atılmış, başlangıçta Çin’den ithal edilen malzemeler kullanılmış; zamanla yerli Japon seramikleri tercih edilmiştir.

16.yüzyılda Zen keşişi Sen no Rikyū çay törenini daha da geliştirerek onu özgün bir sanat formuna dönüştürmüştür. 19. yüzyıldaki Meiji Dönemi’ne kadar çay törenleri yalnızca erkeklere açıktı. Japonya’nın Batı’ya açılmasıyla birlikte kadınlar da törenlere katılmaya başlamıştır.

Zen Budizmi’nin içsel aydınlanma ve ruhsal arınmaya vurgu yapan öğretilerinden ilham alan çay töreni; sadelik, alçakgönüllülük, saygı ve dinginlik gibi değerleri simgeler. Saflık ve temizlik ritüeli olarak kabul edilir. Tören sırasında misafirler gündelik hayatın yüklerinden uzaklaşarak içsel düşünceye yönelirler.

Çay töreninin her unsuru önceden titizlikle planlanır: bahçenin düzenlenmesinden çay odasının döşenmesine kadar. Süreç; malzemelerin hazırlanması, ocağın yakılması, suyun ısıtılması, çayın hazırlanması ve misafirlere sunulmasını kapsar. Günümüz Japonya’sında hâlâ uygulanan geleneksel bir çay töreni yaklaşık dört saat sürebilir ve chashitsu adı verilen özel odalarda gerçekleştirilir.

Törende kullanılan temel araçlar şunlardır: su ısıtmak için furo (mangal), çay kazanı chagama, çayı karıştırmak için bambu fırça chasen, çayın içildiği kâse chawan, toz çayın saklandığı kap natsume.

Çay odasına girmeden önce misafirler dünyevi zenginlik, güç veya şiddeti simgeleyen takı ve silah gibi eşyaları dışarıda bırakırlar. Bu, ruhsal eşitlik ve tevazuyu vurgular. Ev sahibi Tsukegasa adı verilen özel bir kimono giyer ve dizleri üzerinde zarif, sakin hareketlerle töreni yürütür; önce tatlı ve şekerlemeler sunar.

Uzun bambu kaşıkla toz çay kâseye konur, sıcak su eklenir ve bambu fırça ile çırpılır. Misafir çaydan bir yudum aldıktan sonra kâsenin kenarını siler, yanındaki misafire selam vererek kâseyi devreder. Geleneksel olarak çay, tek bir kâseden paylaşılarak içilir; bu eşitlik ve uyumu simgeler.

Tüm misafirler içtikten sonra tören araçlarını inceler ve takdir sözleri söylerler. “Uygunluk sanatı” olarak tanımlanan çay töreninde, ev sahibi ve misafirler sanki son kez buluşuyormuş gibi karşılıklı saygı içinde davranırlar. Tören, ev sahibinin misafirlerini uğurlamasıyla sona erer.

Çay töreninde estetik ve felsefi ilkeler her ayrıntıya işlemiştir. Çay kaseleri çoğu zaman bilerek asimetrik veya kusurlu yapılır; bu, geçiciliği ve kusurdaki güzelliği yücelten wabi-sabi anlayışını yansıtır. Çay evine giden bahçe yolu roji, taş düzenlemeleriyle ziyaretçiyi yavaşlatır ve zihni meditasyona hazırlar. Törenin merkezinde, her karşılaşmanın biricik olduğunu vurgulayan ichigo ichie kavramı bulunur. Çiçekler, duvar yazısı (kakemono), araçlar ve tatlılar mevsime göre seçilir. Ev sahibinin yavaş ve bilinçli hareketleri katılımcıları farkındalığa yönlendirir. Günümüzde çay töreni yalnızca geleneksel bir sanat değil, aynı zamanda kültürel ve ahlaki eğitim aracı olarak öğretilmektedir.

Japon çay töreni, Zen Budist felsefesi, estetik incelik ve sosyal ritüelin benzersiz birleşimini temsil eder. Farkındalık, uyum ve saygıya verdiği önemle basit bir eylemi derin bir kültürel deneyime dönüştürür. 15. yüzyıldan günümüze uzanan bu gelenek, Japonya’nın ruhsal ve sanatsal mirasının yaşayan bir ifadesi olmaya devam etmektedir.

Dr. Hümeyra Türedi

Kaynak: Japanese Wind in the Ottoman Palace (2013), TBMM Milli Saraylar Koleksiyonları.