Japan was the fourth country in the world to produce porcelain, following China, Vietnam, and Korea. Distinguished by their unique forms, decorative motifs, and technical innovations, Japanese porcelains not only developed a distinctive artistic identity but also became a major source of inspiration for both Asian and European ceramic traditions. Within the global history of porcelain, Japanese wares constitute the most original group after Chinese porcelain. Their widespread recognition in Europe today reflects centuries of artistic exchange, trade networks, and shifting cultural tastes—processes that also deeply influenced Ottoman court culture.

The foundations of Japanese porcelain production were laid in the aftermath of the Japanese–Korean War of 1597–1598. A Korean porcelain master known in Japan as Kanegae Sanpei (Ri Sanpei) was brought from Korea to Japan and is regarded as the figure who initiated porcelain production in the country. Ri Sanpei, who had assisted lost Japanese soldiers in Korea, traveled with them to Nabeshima-han on Kyushu Island, one of Japan’s four main islands. There, he quickly gained the trust of the local ruler (the Tonosama of Nabeshima) and began residing in the lord’s palace.

As a skilled porcelain craftsman, Ri Sanpei expressed his desire to establish a porcelain workshop in Japan. With the Tonosama’s approval, he was granted permission to conduct research into porcelain production. The region was deemed ideal due to its abundant water resources and surrounding forests and mountains. In 1616, Ri Sanpei discovered kaolin, the essential raw material for porcelain, in the settlement of Arita, thus marking the true beginning of Japanese porcelain manufacture.

Initially founded by eighteen porcelain craftsmen, Arita soon expanded into a settlement of 200–300 households, including artisans and their families. In Arita, craftsmen combined the porcelain techniques they had practiced in Korea with knowledge acquired from China, developing a new style suited to Japanese tastes. Although porcelain production was a collaborative process and the identity of the first individual maker remains unknown, Ri Sanpei is widely recognized as the most prominent and authoritative porcelain master of Arita. He died in 1655 in Arita, where his grave and a monument erected in his honor still stand. Each year, official commemorations and a porcelain festival are held in his memory with the participation of local authorities and residents.

Later, Japanese porcelains were exported to the world through Dejima Island, located in Nagasaki on Kyushu Island. The name Dejima (De-Shima) means “exit island.” Construction of this fan-shaped artificial island began in 1634 and was completed in 1636, covering an area of approximately 15,000 square meters. During the Edo Period (1603–1868), when Japan severed most foreign relations, Dejima served as the country’s sole point of contact with the outside world for nearly two centuries.

Dejima was created by land reclamation and was initially intended to control Portuguese Christian missionaries. In 1639, following a government decree rejecting Portuguese presence, the island was cleared of Portuguese traders. The Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, had long been engaged in trade between Japan and Europe. The Dutch, previously based in the Hirado region, relocated their trading post to Dejima in 1641. Through the VOC, Japanese porcelains began to be exported to Europe and the Middle East.

The first shipment of Japanese porcelain departed Dejima on 12 October 1657 and reached a Dutch port in July 1658, after an eleven-month journey. Until Japan officially opened its borders to foreign trade in 1859, all Japanese porcelain exports to Europe passed through Dejima. About the route, Imari Port should also be emphasized. The porcelain was produced in Arita and then transported by land and river routes to Imari Port. From there, it was shipped to Nagasaki, where Dejima was located, and through this artificial island of Dejima, the Dutch exported porcelain to Europe.

Japanese Porcelain in the European and Ottoman Markets

In 1644, political instability in China halted porcelain production and exports, leaving European and Middle Eastern markets without their primary supplier. To meet demand, Dutch merchants substituted Chinese porcelain with Japanese wares, which soon gained prominence. By 1658, Japanese porcelains gradually replaced Chinese wares in Europe and the Middle East. As European countries grew wealthier in the seventeenth century, porcelain became a symbol of status, widely purchased for palaces and residences. Consequently, Japanese-made goods and Japanese culture became fashionable across Europe and the Middle East.

This trend also influenced the Ottoman court. Ottoman sultans showed a strong preference for Japanese porcelains, a fact reflected in the approximately 700 Japanese porcelain objects preserved today in the Topkapı Palace collection. Japanese porcelains began to be used in the Ottoman court during the reign of Sultan Mehmed IV (1648–1687). These early examples were produced in Arita and exported to Europe. Archival documents dated 1835 reveal that 85% of the porcelains exported from Imari Port were Arita products, with the remainder consisting of wares from Hasami, Mikawachi, and Karatsu.

Although produced in Arita, these porcelains were known in Europe and the Middle East as Imari porcelains, named after the port city where they were loaded for export. This naming practice underscores the role of maritime trade routes in shaping artistic terminology.

Use and Adaptation of Japanese Porcelain in the Ottoman Court

Unlike European courts, where Japanese porcelains were primarily used for decorative and architectural purposes, early Ottoman usage emphasized functionality. In the Topkapı Palace, Japanese porcelains served as soup bowls, rice dishes, compote bowls, sherbet vessels, jam jars, and pickle containers at the sultan’s table.

Arita porcelains produced between 1655 and 1740 were predominantly blue-and-white and executed using underglaze techniques. Although less common, some pieces featured overglaze decoration in gold, silver, and red. Classic red-ground Imari porcelains, produced between 1690 and 1740, employed a palette of six colors: underglaze cobalt blue combined with overglaze red, light red, gold, green, and yellow.

A typical blue-white Arita porcelain

A classical colourful Imari porcelain

Japanese porcelain and ceramics are typically decorated with motifs carrying symbolic meanings such as power, health, longevity, good fortune, and the transience of life. These include figures of cranes, sea turtles, butterflies, and dragons, as well as designs featuring plum trees, pine trees, bamboo, cherry blossoms, chrysanthemums, and peonies, along with female figures dressed in traditional kimono attire.

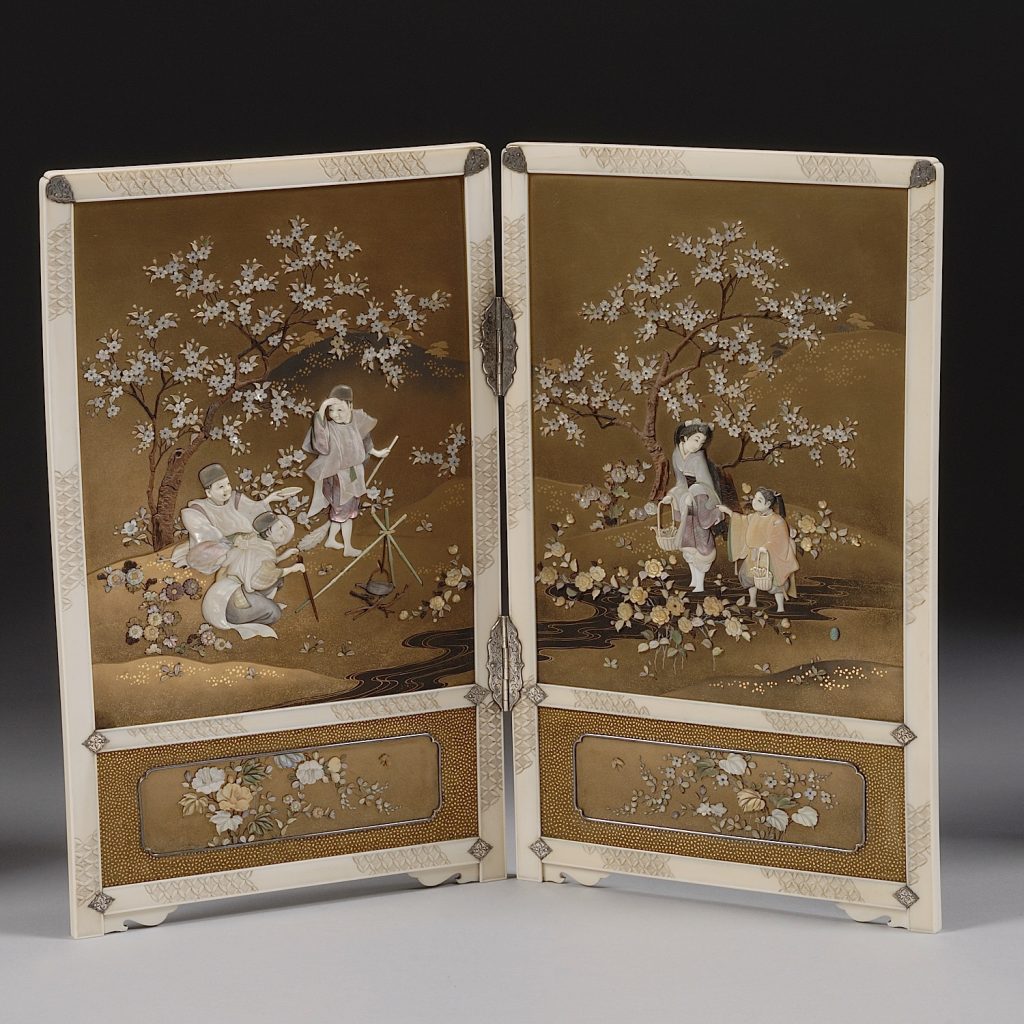

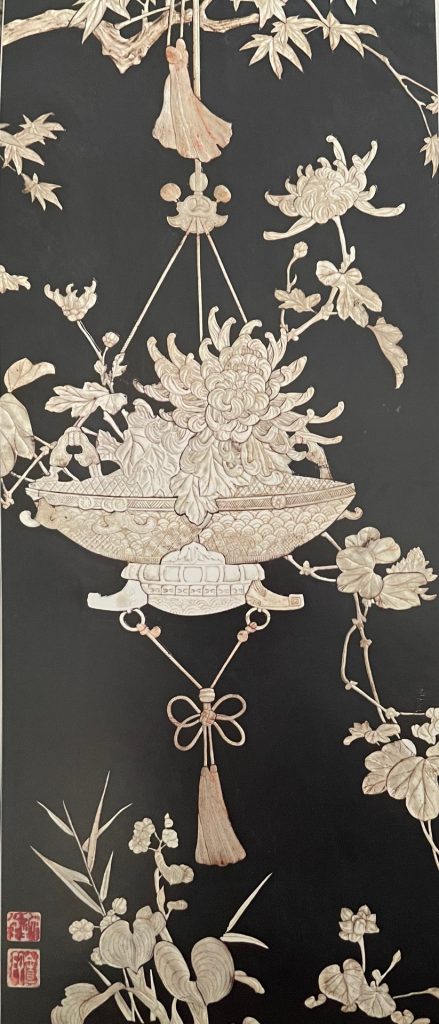

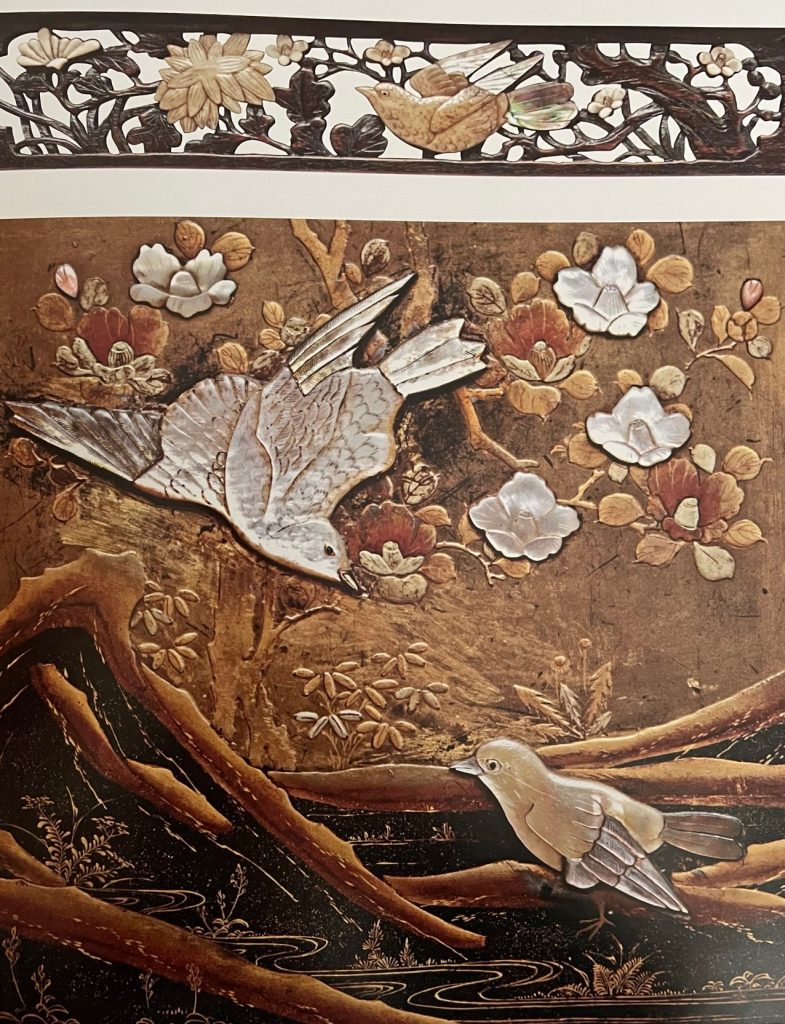

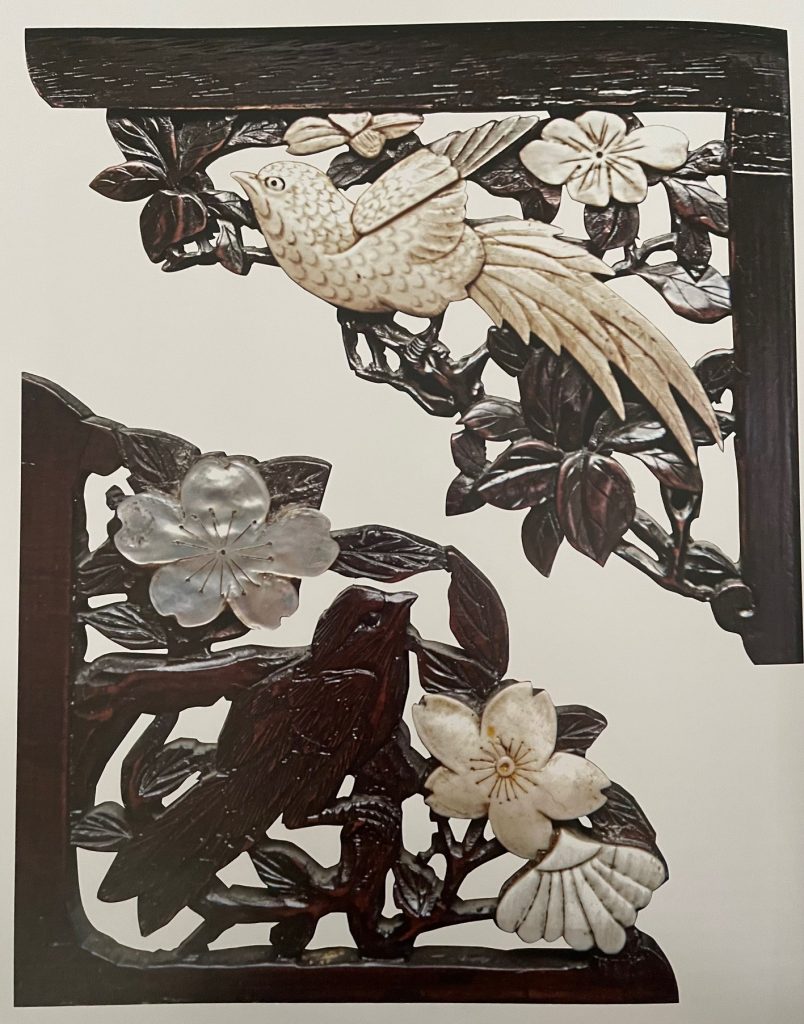

Among furniture examples reflecting Japanese aesthetics, the Shibayama technique is the most frequently encountered and the one most admired by foreign audiences. Some of the finest examples of Shibayama workmanship are preserved in Dolmabahçe Palace.

Shibayama work consists of figures and motifs created through inlay techniques using materials such as gold, mother-of-pearl, ivory, coral, and tortoiseshell, applied onto a surface covered with Japanese gourd (or lacquered base). The motifs most commonly employed include animal figures such as birds and butterflies, as well as floral designs.

A defining characteristic of Shibayama art lies in its profound engagement with the natural world. Rooted in traditional Japanese aesthetics and an awareness of seasonal rhythms, Shibayama craftsmen developed a symbolic visual vocabulary in which flowers, insects, and birds functioned as carriers of cultural meaning rather than ornamental details.

These elements were never purely decorative. Instead, they conveyed layered narratives—expressing philosophical ideas, emotional states, and values deeply embedded in Japanese cultural thought. The careful placement of each motif within a composition reflects not only exceptional technical skill but also a refined poetic sensitivity.

Floral motifs occupy a central position in Shibayama design and are often arranged in fluid, rhythmical groupings across objects such as vases, caskets, and decorative panels. Each flower was selected with intention, carrying associations tied to seasonality and symbolism:

- Chrysanthemum (kiku) signifies longevity and imperial authority and frequently appears in autumn-themed compositions.

- Peony (botan), regarded as the “king of flowers,” embodies wealth, prestige, and refined beauty.

- Plum blossom (ume) represents endurance and moral purity, blooming at the threshold between winter and spring.

- Cherry blossom (sakura), the most emblematic of Japanese flowers, evokes the transient nature of life and the aesthetic of impermanence (mono no aware).

The presence of these blossoms was rarely incidental; rather, they often corresponded to the season, function, or ceremonial context for which the object was produced.

Animal imagery—particularly birds and insects—plays an equally significant role in Shibayama compositions. Their movement introduces vitality into the designs, while their symbolic associations deepen interpretive meaning:

- Cranes (tsuru) symbolize peace, loyalty, and longevity and are commonly depicted as paired figures.

- Swallows and sparrows are linked to affection, joy, and the arrival of spring.

- Butterflies signify transformation, elegance, and the soul within both Shinto and Buddhist traditions.

- Dragonflies convey courage and triumph, qualities historically admired in samurai culture.

Shibayama artisans frequently portrayed these creatures in lively, naturalistic poses—capturing fleeting moments such as a bird in mid-flight or a butterfly alighting on a branch. This attention to movement and immediacy lends the compositions a vivid, almost cinematic presence, reinforcing the intimate relationship between art, nature, and lived experience.

Through this technique, Japan’s distinctive perception of nature—expressed by asymmetrical, flexible, and dynamic lines—was transferred into the Ottoman palace context by means of everyday functional objects, allowing Japanese landscapes and aesthetic sensibilities to enter Ottoman court life.

You can see some examples of Shibayama works below:

Japanese porcelains generally entered the Ottoman court through European markets. A secondary route involved Arab merchants transporting wares via Yemen and the Arabian Peninsula to Istanbul. Until the late nineteenth century, no Japanese porcelain entered the Ottoman collection as a diplomatic gift, reflecting the limited political and economic relations between the two states at the time.

Some Japanese porcelains were modified by European artisans with gold or silver mounts to enhance their value and adapt them to Ottoman usage. Bottles were fitted with metal spouts to resemble ewers or pitchers; bowls received silver lids; and vases were placed on metal bases, resulting in hybrid objects that combined Japanese, European, and Ottoman aesthetics. Silver mounts bearing European hallmarks attest to their Western origin, while certain gilded silver fittings reflect the craftsmanship of Ottoman palace workshops.

Blue-and-white porcelains in Topkapı Palace date primarily to the reigns of Sultan Mehmed IV and Sultan Suleiman II (1687–1691), while colored Imari wares correspond to later sultans, including Ahmed II, Mustafa II, Ahmed III, and Mahmud I. Ottoman sultans referred to Asian porcelains as “white gold”, storing them in treasury depots when not in use. Broken pieces were carefully repaired by palace artisans; irreparable fragments were skillfully reworked with metal additions.

In the nineteenth century, Japanese porcelains were transferred from Topkapı Palace to Dolmabahçe Palace during the reign of Sultan Abdülmecid, and later to Yıldız Palace under Sultan Abdülhamid II. From this period onward, porcelains were no longer used at the sultan’s table but displayed decoratively throughout palace interiors—on consoles, in corridors, near staircases, fireplaces, mirrors, fountains, and ceremonial halls.

Although Dolmabahçe, Yıldız, and Beylerbeyi Palaces were nineteenth-century structures, many of the Japanese porcelains displayed there dated back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, having been relocated from Topkapı Palace. Following Sultan Abdülhamid II’s deposition in 1909, all Japanese porcelains at Yıldız Palace were returned to the Topkapı Palace Treasury.

The presence of seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century Japanese porcelains within a single Ottoman collection reflects the enduring appreciation of these objects by Ottoman sultans and their adaptive use over time. From functional tableware to decorative symbols of prestige, Japanese porcelains occupied a dynamic role in Ottoman court life. Their journey—from Arita workshops through Dejima, European markets, and finally Ottoman palaces—embodies a rich narrative of global exchange, artistic transformation, and cultural continuity that situates Japanese porcelain at the heart of early modern and modern transregional art history.

Dr.Humeyra Turedi

References

Japanese Wind in the Ottoman Palace (2013). TBMM Collections of National Palaces.

Japon Porseleni: Üretimi, Küresel Dolaşımı ve Osmanlı Sarayındaki Karşılanışı

Japonya, Çin, Vietnam ve Kore’den sonra dünyada porselen üreten dördüncü ülkedir. Kendine özgü formları, bezeme repertuarı ve teknik yenilikleriyle Japon porselenleri yalnızca ayrı bir sanatsal kimlik geliştirmekle kalmamış, aynı zamanda hem Asya hem de Avrupa seramik gelenekleri için önemli bir ilham kaynağı olmuştur. Küresel porselen tarihi içinde Çin’den sonra en özgün grubu Japon porselenleri oluşturur. Günümüzde Avrupa’da yaygın biçimde tanınmaları, yüzyıllar boyunca süren sanat alışverişlerinin, ticaret ağlarının ve değişen estetik zevklerin sonucudur. Bu süreçler Osmanlı saray kültürünü de derinden etkilemiştir.

Japon porselen üretiminin temelleri 1597–1598 Japon–Kore Savaşı sonrasında atılmıştır. Japonya’da Kanegae Sanpei adıyla bilinen Koreli usta Ri Sanpei, Japon porselenciliğinin kurucusu kabul edilir. Kore’de kaybolan Japon askerlerine yardım etmiş, ardından onlarla birlikte Kyushu Adası’ndaki Nabeshima Beyliği’ne gitmiştir. Burada yerel bey olan Tonosama’nın güvenini kazanmış ve sarayında yaşamaya başlamıştır.

Usta bir porselenci olan Ri Sanpei, Japonya’da bir porselen atölyesi kurmak istediğini belirtmiş ve izin almıştır. Bol su kaynakları, orman ve dağlarla çevrili bölge üretim için uygun görülmüştür. 1616’da Arita’da kaolin madenini keşfetmesiyle Japon porselen üretimi fiilen başlamıştır.

Başlangıçta 18 usta ile kurulan Arita, kısa sürede 200–300 haneli bir yerleşime dönüşmüştür. Burada Kore’de uygulanan teknikler ile Çin’den öğrenilen bilgiler birleşerek Japon zevkine uygun yeni bir üslup doğmuştur. Ri Sanpei 1655’te Arita’da ölmüş; mezarı ve anıtı hâlen buradadır. Her yıl onun adına törenler ve porselen festivali düzenlenir.

Japon porselenleri dünyaya Nagasaki’deki Dejima Adası üzerinden ihraç edilmiştir. “Çıkış adası” anlamına gelen Dejima, 1634–36 arasında inşa edilmiş yapay bir adadır. Edo Dönemi’nde Japonya’nın dış dünya ile tek temas noktası olmuştur. Başlangıçta Portekizli misyonerleri kontrol etmek amacıyla kurulmuş, 1641’de Hollandalı VOC şirketine tahsis edilmiştir. Japon porselenleri VOC aracılığıyla Avrupa ve Ortadoğu’ya taşınmıştır.

İlk sevkiyat 1657’de yola çıkmış, 1658’de Hollanda’ya ulaşmıştır. 1859’a kadar Avrupa’ya giden tüm Japon porselenleri Dejima üzerinden geçmiştir. Arita’da üretilen porselenler önce İmari Limanı’na, oradan Nagasaki’ye ve Dejima’ya taşınmıştır.

Avrupa ve Osmanlı Pazarlarında Japon Porseleni

1644’te Çin’deki siyasi kriz üretimi durdurunca, Avrupa ve Ortadoğu’daki talebi Hollandalılar Japon porselenleriyle karşılamıştır. 17. yüzyıldan itibaren Japon porselenleri moda olmuş, saraylarda statü sembolü hâline gelmiştir.

Bu eğilim Osmanlı sarayını da etkilemiştir. Topkapı Sarayı’nda bugün yaklaşık 700 Japon porseleni bulunmaktadır. İlk kullanım IV. Mehmed dönemine uzanır. 1835 arşiv belgelerine göre İmari’den çıkan porselenlerin %85’i Arita yapımıdır.

Avrupa’da ve Ortadoğu’da bu porselenler “İmari porseleni” olarak adlandırılmıştır; oysa İmari üretim değil sevkiyat limanıdır.

Osmanlı Sarayında Kullanım

Avrupa’da daha çok dekoratif kullanılan Japon porselenleri, erken Osmanlı’da sofra eşyası olarak kullanılmıştır: çorba kasesi, pilav çanağı, hoşaf tası vb.

1655–1740 Arita porselenleri çoğunlukla mavi-beyazdır. 1690–1740 arası kırmızı zeminli İmari porselenleri altı renkli paletle üretilmiştir.

Motifler güç, sağlık, uzun ömür, şans ve fanilik sembolleridir: turna, kaplumbağa, kelebek, ejder, erik, çam, bambu, sakura, krizantem, şakayık, kimonolu kadın figürleri.

Dolmabahçe Sarayı’nda Japon estetiğini yansıtan mobilyalarda Shibayama tekniği dikkat çeker. Altın, sedef, fildişi, mercan ve bağa kakmalarla yapılır. Motifler kuşlar, kelebekler ve çiçeklerdir. Bu teknik Japon doğa algısını Osmanlı saray yaşamına taşımıştır.

Porselenler genellikle Avrupa pazarlarından alınmış, bazıları Yemen ve Arap tüccarlar yoluyla gelmiştir. 19. yüzyıla kadar diplomatik hediye yoktur.

Avrupalı ustalar bazı porselenleri altın-gümüş montürlerle Osmanlı kullanımına uyarlamıştır: şişeler ibrik formuna, kaseler kapaklı kaplara dönüşmüştür.

Abdülmecid döneminde Dolmabahçe’ye, Abdülhamid döneminde Yıldız Sarayı’na taşınmış; bu tarihten sonra sofrada değil dekoratif kullanılmıştır. 1909’da yeniden Topkapı’ya getirilmiştir.

17., 18. ve 19. yüzyıl Japon porselenlerinin aynı koleksiyonda bulunması, Osmanlı sultanlarının bu eserlere duyduğu kalıcı ilgiyi gösterir. Arita’dan Dejima’ya, oradan Avrupa’ya ve Osmanlı saraylarına uzanan yolculuk, küresel sanat dolaşımının ve kültürel etkileşimin güçlü bir örneğidir.

Dr. Hümeyra Türedi

Kaynak: Japanese Wind in the Ottoman Palace (2013), TBMM Milli Saraylar Koleksiyonları.