1917 Bolşevik Devrimi ile 1953’te Stalin’in ölümüne kadar geçen süreçte Sovyet liderliği, görsel kültürü ideolojik bir araç olarak kullanarak köklü bir toplumsal dönüşüm hedeflemiştir. Victoria E. Bonnell’in Iconography of Power (California Üniversitesi Yayınları) adlı çalışmasında vurguladığı üzere, bu dönem boyunca üretilen görsel propaganda, yalnızca estetik bir uğraş değil; toplumu yeniden biçimlendirme amacını güden bilinçli bir ideolojik projedir. Her poster, heykel ya da sembol, ideal Sovyet yurttaşı olan homo sovieticus’un yaratım sürecinin bir parçasıdır. Bu makale, Sovyet görsel ikonografisinin politik işlevlerini ve ulusal mitleri nasıl dönüştürdüğünü Bonnell’in kitabı üzerinden inceleyelim.

Bonnell’e göre Bolşevikler, geçmiş, şimdi ve gelecek arasındaki anlam ilişkisini yeniden kurgulamak amacıyla yeni bir sembolik düzen inşa etmeye çalışmışlardır. Bu süreçte icat edilmiş gelenekler (Hobsbawm) devreye girer: Zamanla değişmediği izlenimi veren, tekrar eden ve halkın kolayca anlayabileceği bu gelenekler, kitlelerin düşünce dünyasını dönüştürme aracıdır.

1897 verilerine göre, kırsal nüfusun %83’ü, kentsel nüfusun ise %55’i okuma yazma bilmemektedir. Bu durum, görsel araçları stratejik propaganda unsurlarına dönüştürmüştür. Ayrıca Rus Ortodoks Kilisesi’nin zengin ikonografik geleneği, Sovyet liderliğinin görsel temsilleri benimsemesini de kolaylaştırır.

Bonnell’e göre Sovyet propaganda görselleri üç temel işleve hizmet eder:

- Yeni bir toplumsal kimliğin inşası: Sınıf temelli bir kolektif kimlik oluşturulması hedeflenir.

- Yeni kurum ve statülerin meşrulaştırılması: Yeni siyasi yapıların tarih içinde “doğal” ve “kaçınılmaz” bir gelişme olarak gösterilmesi sağlanır.

- Toplumsal değerlerin ve inançların sosyalleştirilmesi: Yeni kuşaklara Sovyet ideallerinin benimsetilmesi amaçlanır.

Bu işlevlerin tümü, özellikle görsel temsil yoluyla daha etkili hale gelir. Hatta Bonnell’a göre Fransız Devrimi’nden bile daha yoğun bir siyasal eğitim ve estetik yeniden inşa süreci yaşanmıştır.

Bonnell, Sovyet propaganda görsellerini dört tarihsel döneme ayırır:

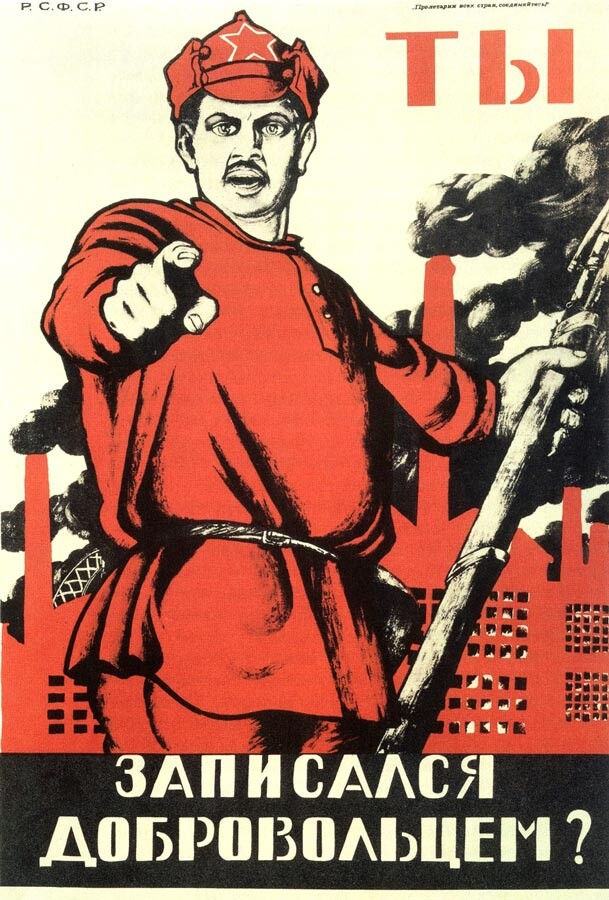

- İç Savaş Dönemi (1918–1921): Aciliyet, kahramanlık ve devrim öne çıkar.

- Stalin Öncesi Dönem (1920’ler): Sınıf mücadelesi ve sanayileşme vaatleri ön plandadır.

- II. Dünya Savaşı Dönemi (1941–1945): Fedakârlık, milliyetçilik ve faşizm karşıtlığı işlenir.

- Yüksek Stalin Dönemi (1946–1953): Stalin, mitolojik bir tanrı-kral olarak temsil edilir; ütopyacı imgeler yaygındır.

1930’lu yıllardan itibaren tüm resmi posterler hem sanatçının hem de devlet kurumunun adıyla yayınlanmış, propaganda merkezileştirilmiştir.

Bonnell çalışmasında dört ana ikonografik tipi analiz eder:

- İşçi İkonu:

Başlangıçta demirci figürüyle özdeşleştirilen işçi, zamanla soyut bir kahramana dönüşür. Geçmişle bağ kurmak ve geleceğe yön vermek amacıyla kullanılır. - Kadın İkonu:

İlk yıllarda alt pozisyonda olan kadın figürü, 1930’lardan itibaren kolektivizasyonun bir parçası olarak öne çıkar. Ancak çoğu zaman hâlâ ataerkil bir çerçevede sunulur. - Lider İkonu (Lenin ve Stalin):

Lenin’in ölümünden sonra imgeleri yaygınlaşır, fakat 1930’lardan itibaren Stalin, onu da kapsayacak şekilde mitolojik bir figüre dönüşür: Yaşayan Tanrı, Babamız Stalin. - Düşman İkonu:

İç ve dış düşmanlar grotesk, karikatürize ya da hayvansı figürlerle betimlenir. Bu ikonografi, Soğuk Savaş mantığının ikili yapısını da destekler.

II. Dünya Savaşı sonrası propaganda, Sovyet halkına cennetin dünyada var olduğunu telkin eder. “Hayaller gerçek oldu” sloganlarıyla yayımlanan posterler, 1950 yılında 300.000 adet basılmıştır. Halkın zihninde Stalin, ölümsüz, hatasız ve kutsal bir lider olarak yerleşir. Bu dönemde ideolojik vurgu, sınıf savaşımından vatan sevgisine kayar; Stalin figürü “Anavatan” ile özdeşleştirilir

Görsel propaganda, kolektif hafızanın ve kimliğin şekillendiği bir araç haline gelir. Bonnell’in tespitlerine göre 1930 öncesinde daha soğuk, akılcı bir görsellik hâkimken, 1940’lardan itibaren duygusal ve duygulandırıcı bir dil benimsenmiştir.

Sonuç olarak, Victoria Bonnell’in çalışması, Sovyet görsel propagandasının yalnızca bir sanat etkinliği olmadığını, aksine bir iktidar dili olduğunu göstermektedir. Tekrarlanan imgeler, standardize edilmiş kahramanlar ve duygusal etkiler yoluyla Sovyet rejimi, yurttaşlarının hem kendilerini hem de rejimi algılayışını yeniden inşa etmiştir. Homo sovieticus, yalnızca politik söylemle değil, aynı zamanda estetik düzenlemelerle yaratılmıştır. Bu görsel dilin dikkatli incelenmesi, dönem ideolojisinin nasıl işlediğini ve değiştiğini anlamamıza yardımcı olur.

Dr. Hümeyra Türedi

The Visual Construction of Soviet Identity: Iconography, Propaganda, and the Making of Homo Sovieticus

Dr. Humeyra Turedi

Between the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution and Stalin’s death in 1953, the Soviet leadership employed visual culture as a deliberate ideological tool to drive a radical social transformation. As emphasized in Victoria E. Bonnell’s Iconography of Power (University of California Press), the visual propaganda produced during this period was not merely aesthetic expression, but a calculated ideological project aimed at reshaping society. Every poster, statue, or symbol was part of the broader process of constructing the ideal Soviet citizen — homo sovieticus. This article examines how Soviet visual iconography functioned politically and transformed national myths, drawing on Bonnell’s work.

According to Bonnell, the Bolsheviks sought to construct a new symbolic order that would redefine the relationship between the past, present, and future. In this process, invented traditions (as theorized by Hobsbawm) played a central role — repetitive, seemingly timeless practices that could be easily internalized by the masses, serving as tools for reshaping collective consciousness.

In 1897, 83% of the rural and 55% of the urban population in Russia were illiterate. This reality elevated the strategic importance of visual media as propaganda tools. Moreover, the rich iconographic tradition of the Russian Orthodox Church facilitated the adoption of visual representation by the Soviet regime.

Bonnell identifies three core functions of Soviet propaganda imagery:

- The construction of a new social identity — Aimed at forming a collective identity based on class.

- The legitimization of new institutions and statuses — Portraying the emerging political structures as “natural” and “inevitable” developments in history.

- The socialization of values and beliefs — Targeting the internalization of Soviet ideals by younger generations.

These functions were enhanced significantly through visual representation. Bonnell even argues that the Soviet project involved a more intense program of political education and aesthetic reorganization than that of the French Revolution.

She categorizes Soviet propaganda into four historical periods:

- Civil War Period (1918–1921): Urgency, heroism, and revolution were emphasized.

- Pre-Stalin Period (1920s): Focus on class struggle and promises of industrialization.

- World War II Period (1941–1945): Emphasis on sacrifice, nationalism, and anti-fascism.

- High Stalinism (1946–1953): Stalin portrayed as a mythic god-king; utopian imagery became widespread.

By the 1930s, all official posters were published with the names of both the artist and the state agency, signaling the centralization of propaganda.

Bonnell analyzes four major iconographic types:

- The Worker Icon: Initially depicted as a blacksmith, the worker figure gradually became an abstract hero symbolizing both historical continuity and future progress.

- The Woman Icon: Women were initially presented in subordinate roles, but from the 1930s onward, they were featured more prominently as symbols of collectivization — though still within patriarchal frames.

- The Leader Icon (Lenin and Stalin): After Lenin’s death, his imagery spread widely, but by the 1930s, Stalin had subsumed even Lenin’s image, emerging as a mythic, godlike “Father of the Nation.”

- The Enemy Icon: Both internal and external enemies were depicted as grotesque, caricatured, or animalistic — reinforcing the Cold War’s dualistic mindset.

Post-WWII propaganda aimed to persuade Soviet citizens that paradise had been achieved on earth. Posters bearing slogans like “Dreams Have Come True” were mass-produced — 300,000 copies in 1950 alone. In the public imagination, Stalin was enshrined as immortal, infallible, and sacred. During this period, ideological emphasis shifted from class struggle to patriotic devotion, and Stalin’s image merged with that of the Motherland.

Visual propaganda thus became a key instrument for shaping both collective memory and identity. According to Bonnell, the pre-1930 imagery was colder and more rational, while from the 1940s onward, a more emotional and sentimental visual language emerged.

In conclusion, Bonnell’s work demonstrates that Soviet visual propaganda was not just an artistic endeavor but a language of power. Through repeated images, standardized heroes, and emotional cues, the Soviet regime reconstructed how its citizens viewed themselves and their government. Homo sovieticus was forged not only through political discourse but also through a meticulously crafted aesthetic order. Studying this visual language provides valuable insights into the operation and evolution of Soviet ideology.