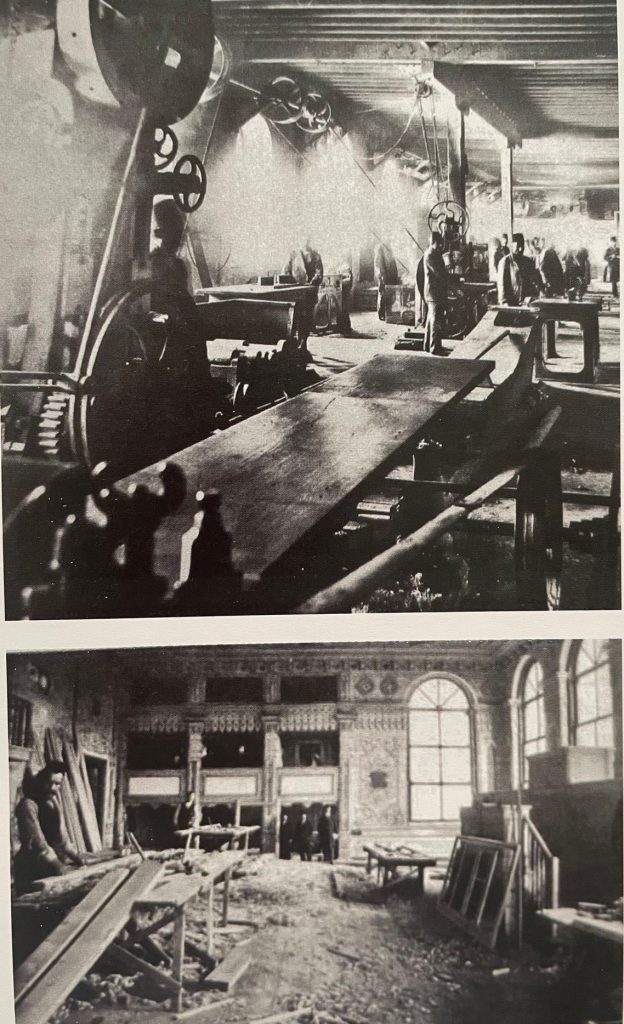

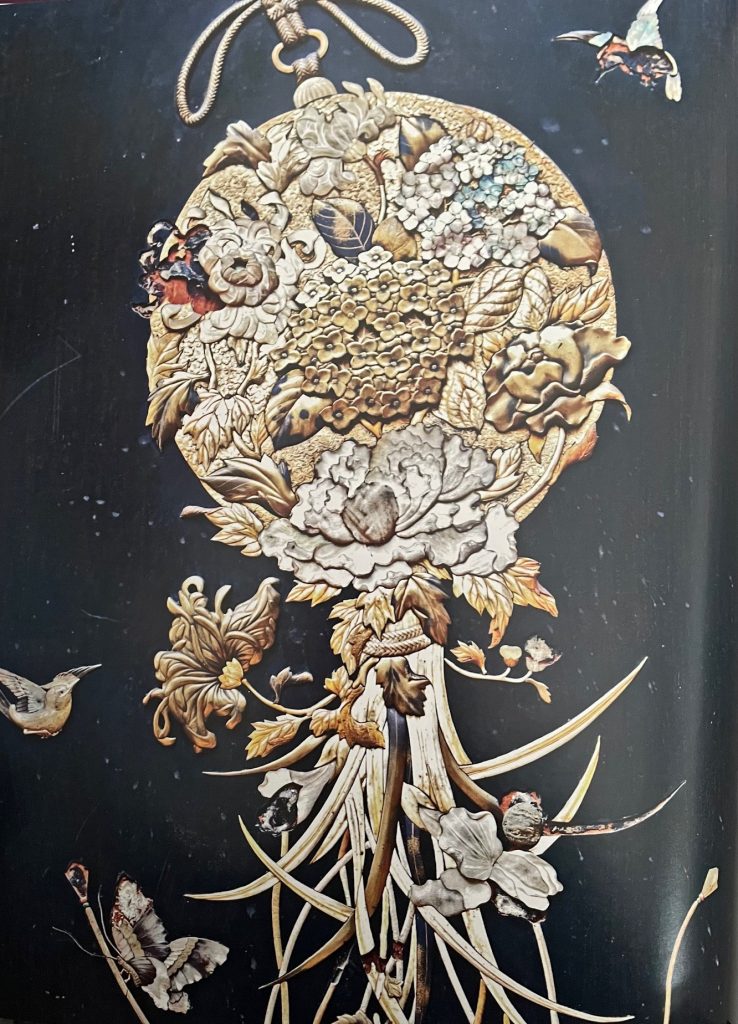

The Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, which houses unique artifacts from Anatolian lands dating back to the Paleolithic Age, is located in two remarkable historic buildings: Mahmutpaşa Bedesteni and Kurşunlu Han, both architectural works from the Ottoman period. Restored and renewed in 2014, the museum offers visitors an immersive historical experience through virtual tours, reconstructions, and replicas, allowing a vivid journey into humanity’s deep past.